October is fire season. While the rest of the country swoons over crisp fall air and Mardi Gras foliage, Southern California braces for color of a different sort. We residents scan painfully blue skies for scribbles of smoke. We examine hillsides furred with browned grass, punctuated with the gray-green eucalyptus trees -- ten-story candles, arboreal dynamite. We wince at forecasts predicting “Santa Ana winds” -- super-heated exhalations from the Mojave Desert which often mark fire season’s opening.

I’ve lived in Southern California my entire life. When I was young, the town I lived in, built in a bowl at the center of bone-dry, high-desert foothills, periodically found itself hostage to wildfire. I remember orange skies and ash falling like snow, a layer of black grit on windowsills and the hoods of cars. The omnipresent smell of burnt vegetation and swimming pools sporting an oily slick of spent fuel.

When I was about ten years old, the street I lived on found itself directly in the path of a wildfire. The houses across the street had backyards bordered by natural hillside, separated from relative wilderness by flimsy chain-link fencing. The fire’s point of origin was somewhere to the west of us, started -- intentionally, we found out later -- in the center of a small state park, and blooming outward. We watched the news for word of the fire’s trajectory, paid close attention to the direction and power of the wind. As this was before e-mail, before home computers, before reverse-911 alerts, the information we gleaned was attenuated; it was still possible, despite the orange skies, to feel somewhat removed from the action.

Then we noticed the fire trucks. Five, then six, then seven of them. Converging on our little neighborhood, their shiny red bulk diminishing our homes to mere backdrop. At first, none of the firefighters would talk to us, though we neighborhood kids were dying to talk to them, bouncing up and down on our heels and sprinting back and forth on the sidewalks behind our parents -- our poor parents, whose fear was mostly lost on us, fixated as we were on the firefighters’ uniforms, on their helmets, on their walkie-talkies, the tangible evidence of their importance. Then, receiving word of a shift in the prevailing winds, the firefighters’ focus shifted. A moment of awful, visceral thrill: the firefighters were talking to our parents, telling our parents to pack up and be prepared to leave on their order. We were no longer spectators -- we were the main attraction. We might be on T.V.!

With faces of stone, my parents hustled me and my sister back to our house. We were told we could fill a paper bag each with things from our rooms. At eight and ten, my sister and I did not acquit ourselves particularly well, here: I remember we both stuffed our Barbies and their wardrobes into our bags, but forgot our scrapbooks, our souvenirs. I did have the presence of mind to grab my stuffed rabbit -- named, imaginatively, Bunny -- from its accustomed place on my bed before rocketing out the door, where my parents were waiting in the driveway.

We stood beside our loaded station wagon and watched the firefighters race to the top of our dead-end street, where Little Sugarloaf and Big Sugarloaf (our local names for the neighborhood hills we’d all hiked countless times) could most easily be reached. Our dogs, loaded into the wagon first by my parents (before the photo albums, before my dad’s paintings, before my grandmother’s wedding dress, before my Barbies, for that matter), threw themselves at the windows, barking furiously in an excess of confusion and excitement and doggy-rage. We watched the hill directly across the street.

And then we saw it.

With the speed of water tumbling out of a cup, the fire poured itself over the lip of the hill. Untethered, the fire chewed its way through the brush, through brittle sage and grass and manzanita, a thick spill of red and orange flaring down and out, urged onward by gravity and wind, erasing the usual brown of the hillside. The fire made no sound; it was quiet. Except for the shouts of the firefighters already on the hillside, already in its path, there was nothing to hear. This seemed odd. To my ten-year-old mind, the absence of sound was the scariest bit. Anything moving that fast should have been noisy, should have sounded like a waterfall, like hail, like an engine. This fire was quietly, simply, efficient.

My parents had had enough. We joined our now-hysterical dogs in the station wagon and left.

When we returned to our house several hours later, the only evidence of the fire was a blackened hillside, relieved here and there by the pale gray of scattered boulders, and the smell of ash. The fire was contained quickly, and our neighbors’ homes were spared. Half the kids in the neighborhood vowed to become firefighters when they grew up. And fire season passed.

We are all apprentices in a craft where no one ever becomes a master - Ernest Hemingway

Showing posts with label Lisa Taylor. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Lisa Taylor. Show all posts

Sunday, December 26, 2010

Monday, October 11, 2010

Lisa Taylor - Fire Season

October is fire season. While the rest of the country swoons over crisp fall air and Mardi Gras foliage, Southern California braces for color of a different sort. We residents scan painfully blue skies for scribbles of smoke. We examine hillsides furred with browned grass, punctuated with the gray-green eucalyptus trees -- ten-story candles, arboreal dynamite. We wince at forecasts predicting “Santa Ana winds” -- super-heated exhalations from the Mojave Desert which often mark fire season’s opening.

I’ve lived in Southern California my entire life. When I was young, the town I lived in, built in a bowl at the center of bone-dry, high-desert foothills, periodically found itself hostage to wildfire. I remember orange skies and ash falling like snow, a layer of black grit on windowsills and the hoods of cars. The omnipresent smell of burnt vegetation and swimming pools sporting an oily slick of spent fuel.

When I was about ten years old, the street I lived on found itself directly in the path of a wildfire. The houses across the street had backyards bordered by natural hillside, separated from relative wilderness by flimsy chain-link fencing. The fire’s point of origin was somewhere to the west of us, started -- intentionally, we found out later -- in the center of a small state park, and blooming outward. We watched the news for word of the fire’s trajectory, paid close attention to the direction and power of the wind. As this was before e-mail, before home computers, before reverse-911 alerts, the information we gleaned was attenuated; it was still possible, despite the orange skies, to feel somewhat removed from the action.

Then we noticed the fire trucks. Five, then six, then seven of them. Converging on our little neighborhood, their shiny red bulk diminishing our homes to mere backdrop. At first, none of the firefighters would talk to us, though we neighborhood kids were dying to talk to them, bouncing up and down on our heels and sprinting back and forth on the sidewalks behind our parents -- our poor parents, whose fear was mostly lost on us, fixated as we were on the firefighters’ uniforms, on their helmets, on their walkie-talkies, the tangible evidence of their importance. Then, receiving word of a shift in the prevailing winds, the firefighters’ focus shifted. A moment of awful, visceral thrill: the firefighters were talking to our parents, telling our parents to pack up and be prepared to leave on their order. We were no longer spectators -- we were the main attraction. We might be on T.V.!

With faces of stone, my parents hustled me and my sister back to our house. We were told we could fill a paper bag each with things from our rooms. At eight and ten, my sister and I did not acquit ourselves particularly well, here: I remember we both stuffed our Barbies and their wardrobes into our bags, but forgot our scrapbooks, our souvenirs. I did have the presence of mind to grab my stuffed rabbit -- named, imaginatively, Bunny -- from its accustomed place on my bed before rocketing out the door, where my parents were waiting in the driveway.

We stood beside our loaded station wagon and watched the firefighters race to the top of our dead-end street, where Little Sugarloaf and Big Sugarloaf (our local names for the neighborhood hills we’d all hiked countless times) could most easily be reached. Our dogs, loaded into the wagon first by my parents (before the photo albums, before my dad’s paintings, before my grandmother’s wedding dress, before my Barbies, for that matter), threw themselves at the windows, barking furiously in an excess of confusion and excitement and doggy-rage. We watched the hill directly across the street.

And then we saw it.

With the speed of water tumbling out of a cup, the fire poured itself over the lip of the hill. Untethered, the fire chewed its way through the brush, through brittle sage and grass and manzanita, a thick spill of red and orange flaring down and out, urged onward by gravity and wind, erasing the usual brown of the hillside. The fire made no sound; it was quiet. Except for the shouts of the firefighters already on the hillside, already in its path, there was nothing to hear. This seemed odd. To my ten-year-old mind, the absence of sound was the scariest bit. Anything moving that fast should have been noisy, should have sounded like a waterfall, like hail, like an engine. This fire was quietly, simply, efficient.

My parents had had enough. We joined our now-hysterical dogs in the station wagon and left.

When we returned to our house several hours later, the only evidence of the fire was a blackened hillside, relieved here and there by the pale gray of scattered boulders, and the smell of ash. The fire was contained quickly, and our neighbors’ homes were spared. Half the kids in the neighborhood vowed to become firefighters when they grew up. And fire season passed.

I’ve lived in Southern California my entire life. When I was young, the town I lived in, built in a bowl at the center of bone-dry, high-desert foothills, periodically found itself hostage to wildfire. I remember orange skies and ash falling like snow, a layer of black grit on windowsills and the hoods of cars. The omnipresent smell of burnt vegetation and swimming pools sporting an oily slick of spent fuel.

When I was about ten years old, the street I lived on found itself directly in the path of a wildfire. The houses across the street had backyards bordered by natural hillside, separated from relative wilderness by flimsy chain-link fencing. The fire’s point of origin was somewhere to the west of us, started -- intentionally, we found out later -- in the center of a small state park, and blooming outward. We watched the news for word of the fire’s trajectory, paid close attention to the direction and power of the wind. As this was before e-mail, before home computers, before reverse-911 alerts, the information we gleaned was attenuated; it was still possible, despite the orange skies, to feel somewhat removed from the action.

Then we noticed the fire trucks. Five, then six, then seven of them. Converging on our little neighborhood, their shiny red bulk diminishing our homes to mere backdrop. At first, none of the firefighters would talk to us, though we neighborhood kids were dying to talk to them, bouncing up and down on our heels and sprinting back and forth on the sidewalks behind our parents -- our poor parents, whose fear was mostly lost on us, fixated as we were on the firefighters’ uniforms, on their helmets, on their walkie-talkies, the tangible evidence of their importance. Then, receiving word of a shift in the prevailing winds, the firefighters’ focus shifted. A moment of awful, visceral thrill: the firefighters were talking to our parents, telling our parents to pack up and be prepared to leave on their order. We were no longer spectators -- we were the main attraction. We might be on T.V.!

With faces of stone, my parents hustled me and my sister back to our house. We were told we could fill a paper bag each with things from our rooms. At eight and ten, my sister and I did not acquit ourselves particularly well, here: I remember we both stuffed our Barbies and their wardrobes into our bags, but forgot our scrapbooks, our souvenirs. I did have the presence of mind to grab my stuffed rabbit -- named, imaginatively, Bunny -- from its accustomed place on my bed before rocketing out the door, where my parents were waiting in the driveway.

We stood beside our loaded station wagon and watched the firefighters race to the top of our dead-end street, where Little Sugarloaf and Big Sugarloaf (our local names for the neighborhood hills we’d all hiked countless times) could most easily be reached. Our dogs, loaded into the wagon first by my parents (before the photo albums, before my dad’s paintings, before my grandmother’s wedding dress, before my Barbies, for that matter), threw themselves at the windows, barking furiously in an excess of confusion and excitement and doggy-rage. We watched the hill directly across the street.

And then we saw it.

With the speed of water tumbling out of a cup, the fire poured itself over the lip of the hill. Untethered, the fire chewed its way through the brush, through brittle sage and grass and manzanita, a thick spill of red and orange flaring down and out, urged onward by gravity and wind, erasing the usual brown of the hillside. The fire made no sound; it was quiet. Except for the shouts of the firefighters already on the hillside, already in its path, there was nothing to hear. This seemed odd. To my ten-year-old mind, the absence of sound was the scariest bit. Anything moving that fast should have been noisy, should have sounded like a waterfall, like hail, like an engine. This fire was quietly, simply, efficient.

My parents had had enough. We joined our now-hysterical dogs in the station wagon and left.

When we returned to our house several hours later, the only evidence of the fire was a blackened hillside, relieved here and there by the pale gray of scattered boulders, and the smell of ash. The fire was contained quickly, and our neighbors’ homes were spared. Half the kids in the neighborhood vowed to become firefighters when they grew up. And fire season passed.

Friday, September 17, 2010

Lisa Taylor: Persian Rug

There is an aphorism with roots in the crafting of Persian rugs: perfection belongs to God. The master-weaver, confident in his skill, will intentionally bobble a motif, insert a strand of the wrong shade, botch - slightly - the overall symmetry of a design. The idea is that to produce a piece of art capable of being described as “perfect” by the weaver constitutes usurpation, insult – an invocation of the wrath of the Almighty. Perfection is not the province of humanity. (As with many expressions of religious fervor, it’s a perfect blend of humility and hubris: after all, the master-weaver necessarily begins with the assumption he can, in fact, do it – make the perfect rug. He opts to swerve a bit, thought, for the sake of his immortal soul.)

Hubristic or not, I’ve always liked this approach. The ideal of perfection is often more than enough to keep me from doing anything remotely creative. The image in my head can never be perfectly translated in paint; the model in front of me is never perfectly realized on paper. God knows the point I want to make when I write often looks less than mind-bendingly profound when it hits the computer screen – why, for Christ’s sake, even bother?

Then there’s the matter of my own personal gods, and their damnable perfection. This is often a complicating factor for me. I don’t define myself creatively as a writer (half of you are now saying to yourselves, “No shit, Sherlock, get to the point”). I paint, I draw – and I am happiest in an art museum. I spend a lot of time looking at the beauty other artists create. And I’m here to tell you, perfection can be found outside of the weaving halls of Persia (probably inside them as well: I have no doubt thousands of weavers have tempted Allah’s anger, and produced the exquisite, unable to resist the lure of perfection. I’d like one of those rugs, please).

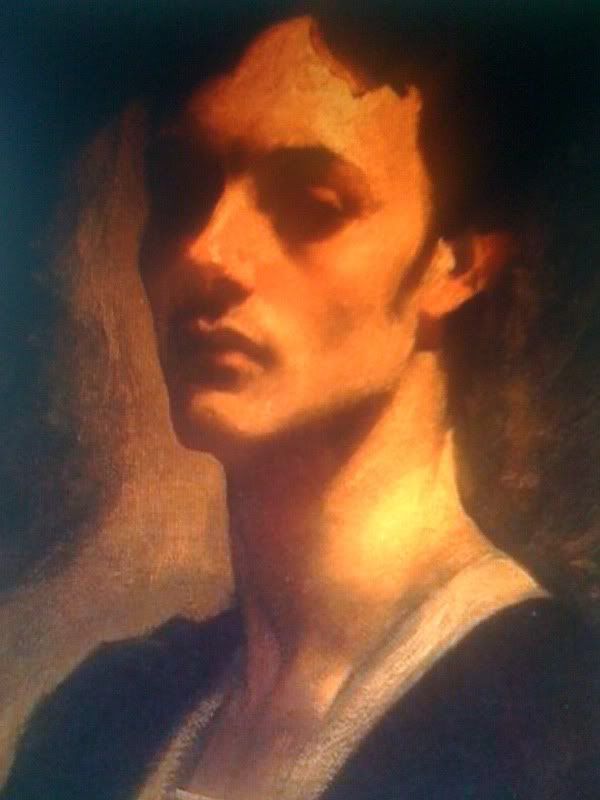

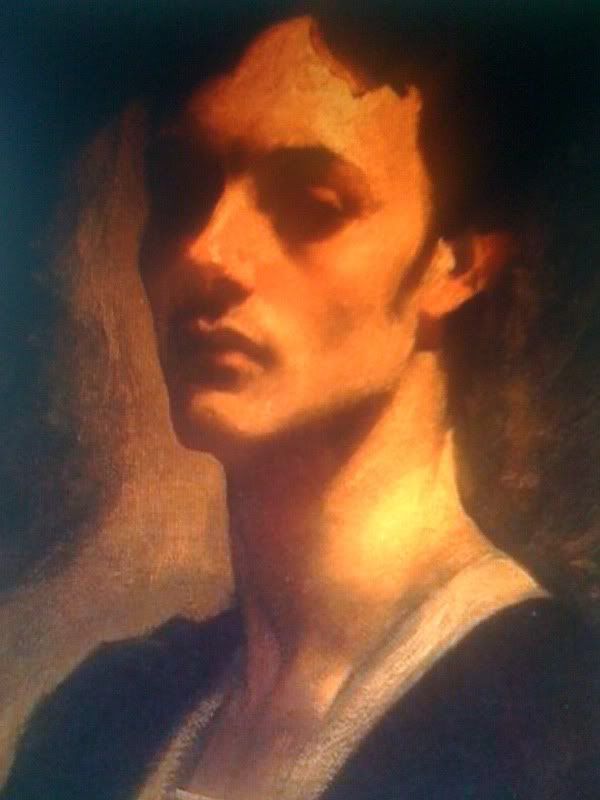

This, to me, is perfection:

John Singer Sargent, Albert De Belleroche.

Equipped with unlimited time and funds and privacy and inspiration and wine and cigarettes and great sex and good background music, still I could never approach this level of beauty in what I do, in what I make.

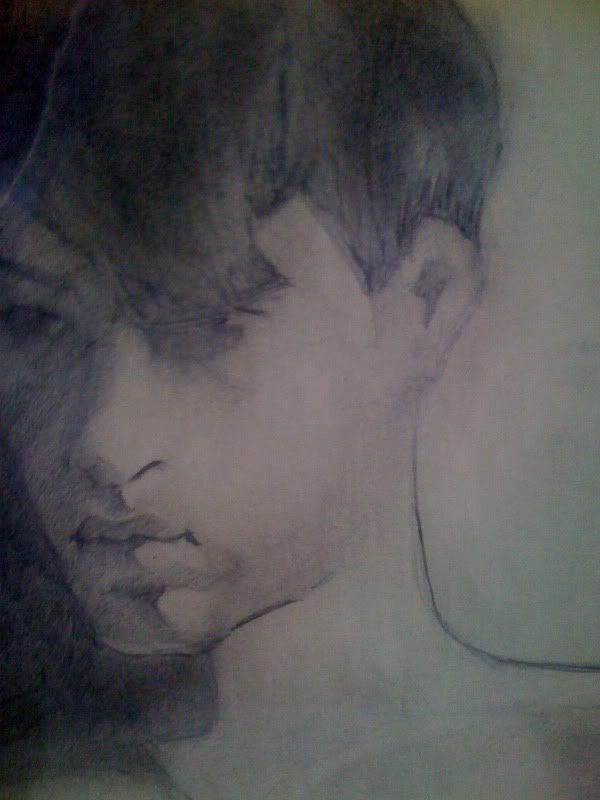

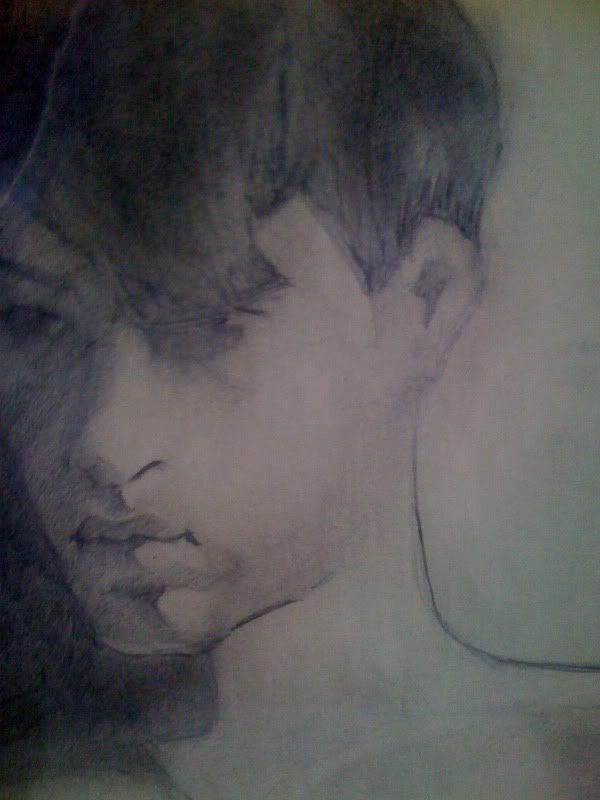

Nevertheless, because I’m human and there are things in my head that want to live in the world and dammit, it feels good, I periodically force the issue. I acknowledge I won’t, I can’t, achieve Sargent-like levels of anything. I put the ideal in a box and the box on a shelf. I get out my pencils. I stare down the blank newsprint. I draw something. I think of the Persian weaver, and I leave perfection to God.

Hubristic or not, I’ve always liked this approach. The ideal of perfection is often more than enough to keep me from doing anything remotely creative. The image in my head can never be perfectly translated in paint; the model in front of me is never perfectly realized on paper. God knows the point I want to make when I write often looks less than mind-bendingly profound when it hits the computer screen – why, for Christ’s sake, even bother?

Then there’s the matter of my own personal gods, and their damnable perfection. This is often a complicating factor for me. I don’t define myself creatively as a writer (half of you are now saying to yourselves, “No shit, Sherlock, get to the point”). I paint, I draw – and I am happiest in an art museum. I spend a lot of time looking at the beauty other artists create. And I’m here to tell you, perfection can be found outside of the weaving halls of Persia (probably inside them as well: I have no doubt thousands of weavers have tempted Allah’s anger, and produced the exquisite, unable to resist the lure of perfection. I’d like one of those rugs, please).

This, to me, is perfection:

John Singer Sargent, Albert De Belleroche.

Equipped with unlimited time and funds and privacy and inspiration and wine and cigarettes and great sex and good background music, still I could never approach this level of beauty in what I do, in what I make.

Nevertheless, because I’m human and there are things in my head that want to live in the world and dammit, it feels good, I periodically force the issue. I acknowledge I won’t, I can’t, achieve Sargent-like levels of anything. I put the ideal in a box and the box on a shelf. I get out my pencils. I stare down the blank newsprint. I draw something. I think of the Persian weaver, and I leave perfection to God.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)